New courses follow four-step approval process, diversify class options

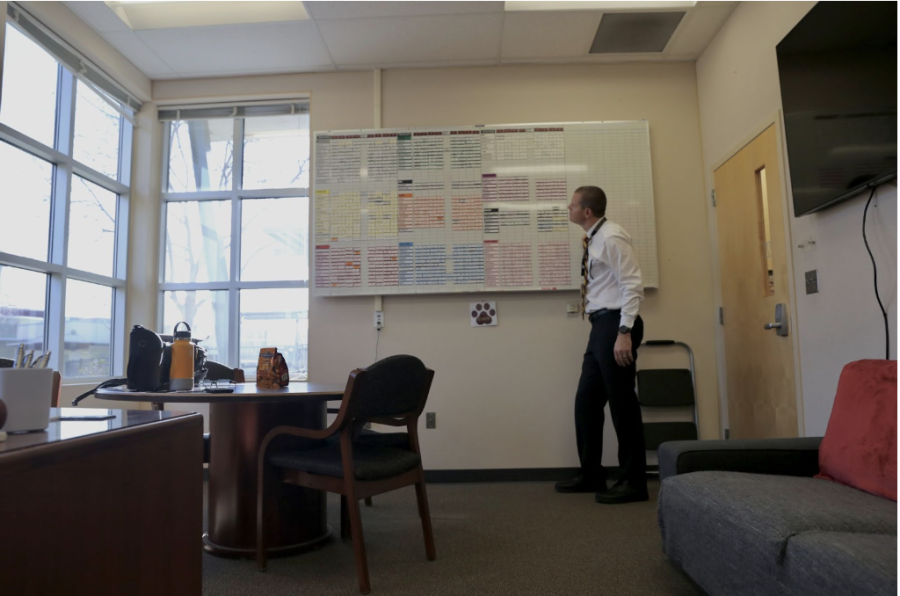

In his office, Principal Mr. Scott Collins reviews the master schedule board. The board contains all classes, also called sections, with their corresponding periods and teachers. As new classes are added over time, administration rearranges and improves the schedule as needed. “We’re working on a lot of new things to try to continue to have a better year and a better master schedule. Classes are a large cultural and academic foundation, and we have to work to make our master schedule better,” Collins said. Photo by Isabella Tomasini.

The Course Preview Days Jan. 24-26 introduced the scheduling process students follow for next year. With more than 120 courses to choose from, making these selections can feel overwhelming, especially as new classes are continually added to the master schedule. Yet, knowing the process of course approval can be helpful for understanding the behind-the-scenes process to help students make selections

New classes follow a process formally known as the New Course Adoption Process, which is a multi-step process involving all levels of school and district staff. First, a course author – sometimes a teacher, principal or other staff member – fills out a proposal. This proposal is then reviewed and approved by the department chair of the potential course, the principal and other members of a council. In a typical school year, this stage usually occurs during October and November.

In the later part of November, the course is then reviewed a second time, in which the impact and importance of the class is discussed. Once the course passes this stage, it is sent to the Board of Trustees for review. The Board reviews the course proposal throughout December and January, and if they formally approve it, the class gets assigned a course code and may also go through A-G certification to have the credits count at UCs and CSUs. The final stage of this process occurs between January and February. This timeline is set to ensure that the course will be fully prepared, staffed and ready for integration by the upcoming fall semester.

In the first stage of development, the ideas for classes can come from a wide range of sources, with each class having idiosyncrasies in the developmental process.

“Different classes may have different processes; some ideas come from the district, some from the staff, some from the principal, some from students. To be honest, each class has a life of its own in that process,” Principal Mr. Scott Collins said.

The level of student interest is a necessary component of the brainstorming process. Mr. Vincent Perez introduced the self defense class and went through the process of course adoption throughout its multiple stages, including gauging student interest.

“If there’s no interest from students then there’s no point in having the class. Generally, I think the teachers initiate [a course] based on the interest or buy-in from the students,” Perez said.

Once the course has been inspired and deemed fitting for the student interest level, the teacher or leader of the proposal will have to submit a complete outline of their vision.

“I had to fill out a big, long packet of information, talking about what we’re covering in the course, the units, the ESAs and the costs,” Perez said.

Collins said that with many moving parts, the steps to become approved are more complicated than the idea stage.

“When we talk about a class that hasn’t even been done before in the district, there are a series of questions about what the class is, what the curriculum is like, what the purpose of it is, and what need it serves,” Collins said. “Is it a class that the UC system is pushing out? Is it a local idea? Is it an A-G? Is it an elective? There’s all those questions surrounding it.”

Curriculum is another hurdle for all potential classes, with no clear-cut way to source material in brand-new courses. For Mrs. Emilie Cavolt, it was a mix of actual course material and research.

“For Introduction to Mindfulness, I applied to Yale University to get some of their materials for my class, so [administration and the RUSD School Board] approved it after the application process. I knew right away that one of the big units would be on the ‘Science of Happiness,’ so that was approved through Yale,” Cavolt said. “But everything else I develop on my own based on what I see other colleges doing, because lots of universities are doing mindfulness classes now.”

Perez also said that the curriculum for his seventh-period self defense class was largely developed independently and based on past experience.

“I’ve grown up wrestling my whole life, so I think a lot of the curriculum is just stuff that I’ve learned through my coaches and just wrestling in general,” Perez said.

To avoid inadvertently pushing out another course with the adoption of a new one, part of the approval process involves considering the implications of adopting the course.

“After the [first] vote, it gets put out to the department chairs to talk about the course in the departments to think about, ‘Will this interfere with the classes already running?’” Cavolt said.

The process of having a new class added isn’t just about curriculum or approvals, though — it’s about cost as well. The amount of available courses, including newly proposed ones, directly correlates the amount of available funding. This funding is determined by numerous variables, including the projected student population (a number which is calculated by the district office using past statistics, middle school enrollment and current 9th-11th graders), daily attendance and specialty programs and demographics.

“Funding starts with attendance; it’s called ADA, or average daily attendance. Every district gets ‘x’ amount of dollars per kid per day they attend. Then, there are other funding sources for other things, [such as] special education, demographic makeup of kids in relation to socioeconomic status, English language learner population, and homeless and foster youth,” Collins said. “The higher number of kids you have that fall into those categories, the more funding the state gives you due to the higher need.”

If a new class gets added and funding isn’t available for existing classes, it is inevitable that a class has to get cut.

“Our school only gets funded to have so many teachers to teach so many classes, and with every section or class that gets added, there is some place where something has to come out,” Collins said.

While the process of adopting a new class is complicated and can take up to five months from the time of proposal – not including the brainstorming and sourcing stages – many teachers who have successfully piloted a new class said they feel it is an important part of serving students and their needs.

Cavolt said, “It’s important for us to offer students something that interests them so there’s a reason to be excited about coming to school. I think pitching new courses and having the opportunity for creativity is what brings life to this campus.”

by ALLIE BOSANO, MAYA GOMEZ & ISABELLA TOMASINI